Theorem 1: Extremism Loses

Passion is powerful. The more passionate your activists, the harder they work.

Passion is correlated to radicalism. Radical party members tend to be more passionate.

Put the two together and you have a strong case for a radical political party. For this reason and others, third parties in the U.S. tend to be radical. Unfortunately for them, this is a near guarantee for failure.

Voters tend to vote for the candidates with whom they agree. A candidate near the center will have more voters in agreement than a candidate off in the radical fringe.

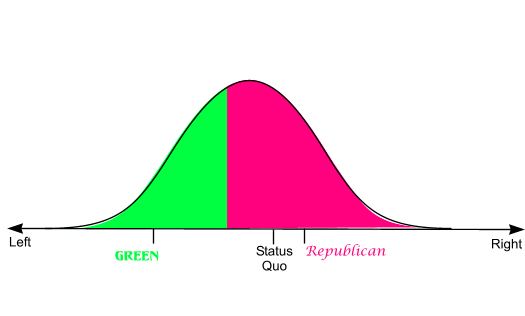

Consider a congressional race in a liberal district. Suppose the radical liberal elements decide to run a radical socialistic Green candidate. Meanwhile, the conservative minority gets behind a barely conservative Republican. And let us suppose there is no Democrat in the race (because the liberal activists got behind the radical Green). If the voters vote for the candidate closest to their views, the Republican wins!

�

Even though the Republican is to the right of the center of this district, the Green is so far to the left that moderate leftists end up voting for the Republican.

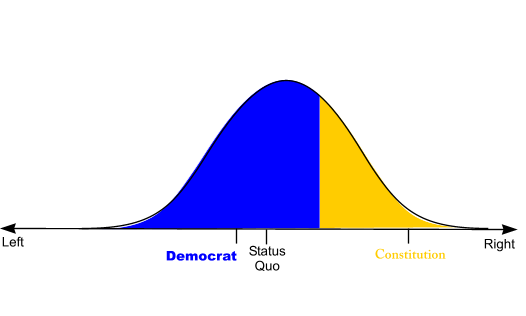

We have the converse scenario with a hard-right Constitution Party candidate vs. a moderately liberal Democrat in a conservative district.

�

In either case, going with the radical party produces election results in the opposite direction of the radical party’s goals! For this reason (and others) most radical liberals hold their noses to support moderate Democrats and most radical conservatives hold their noses to support moderate Republicans.

This leads us to our first rule:

Rule 1: a successful third party must be moderate enough to win somewhere.

This is actually one of the beauties of the American political system: it keeps out the wackos. With district based elections you have to be close enough to the center to be in the mainstream somewhere. This results in a legislature that is sufficiently united to be able to conduct business. With proportional representation Commies and fascists can get elected. Giving the fringe a seat at the table produces rancor in the legislatures, Third World style politics. Dictatorship becomes tempting.

Reforming district-based elections to use approval or range voting is worth pursuing, however. Range voting would bring representatives even further to the center, while allowing exploration of more than two directions from the center.

That said, we will have quite a bit of room for passion and principle in our system. Districts vary. A politician who would be considered a radical leftist by most can still be considered mainstream in places like Berkely California. Furthermore, the model I used in the figures above is approximate.

Even in two-way races, people do not vote purely for ideological agreement. Some liberals in the liberal scenario above may well vote for the radical Green candidate in order to offset the conservatives in other districts. The converse holds for conservatives in the second scenario for the radical Constitution Party candidate. But do note that such sophistication is nowhere close to universal. My observation in the field is that voters in the middle generally go with the candidate closest to their view with little regard to the impact on the total legislature. I have tried the bathtub metaphor with moderate libertarians with little success. (If the tub is too cold, you add unpleasantly hot water in order to bring the overall mixture to the desired temperature. A radical libertarian is like the hot water.)

Some votes are won for reasons other than ideology. People vote for experience, good morals, good looks, pork, special privileges and/or simple name recognition.

And many people don’t bother to vote. Passion makes voting worthwhile. It is easier to get out the votes of your radicals than your swing voters.

For these reasons it is possible to get away with being a bit more radical than the ideology diagrams above would indicate. Combine this with district variance and you have room for a party with ideas and a platform with teeth.

But don’t get carried away! In my conversations with many Libertarian activists, I have encountered many who would deny that Rule 1 has much of any importance. They tell me that platforms don’t matter, that people don’t read platforms, that it’s just about money, publicity, name recognition and getting out the vote.

To this I shout “Balderdash!” We do have many informed voters. News programs have traditionally been among the most popular of the major network offerings. Throw in CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, talk radio and weblogs and then tell me that only a tiny elite cares about political platforms. Yes, there are many people who are ignorant of the issues, and many of them vote. But even among the ignorant, the platform messages get through; many rely on the advice of those who are not ignorant. (See The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell.)

So, while I do not think that a new party needs to appeal to 50% of the voters overall, it does need to appeal to well over 5%. As a rough first guess, I would suggest that a new party should position itself at around the 80th percentile along its scale of values; that is, 20% of the voters are more radical than the party’s position. This should provide at least 5-10% of the voters who are less radical but are still closer to the new party’s position than they are to the major party positions. Throw in district variance and you have a majority position somewhere.

You might be able to get away with being a bit further out, possibly out to the 90% percentile overall. Doing so can increase passion, which is useful for acquiring early adopters, but this also loses mainstream votes.

For comparison, look at the percentile scores of the existing third parties. Prior to the 2006 reforms, I would say that the Libertarian Party had positioned itself above the 99th percentile on the small government scale. That is, fewer than 1% of the U.S. population was more radically libertarian than the Libertarian Party. With the new reforms, the party might be down as far as the 95th percentile. However there are still some pretty radical positions in the platform, deal-killers for most people.

I leave it as an exercise for Green and Constitution Party members to determine what percentiles their parties are positioned at.

Previous

| 1

| 2 | 3

| 4

| 5

| 6

| 7

| 8

| Next

Copyright 2007, Carl S. Milsted, Jr. All rights reserved.

|